If you’re a reader or writer of historical crime fiction,

which is the best period of history to go for? By the best, I mean the worst.

The bloodiest, the most turbulent, vicious and conniving.

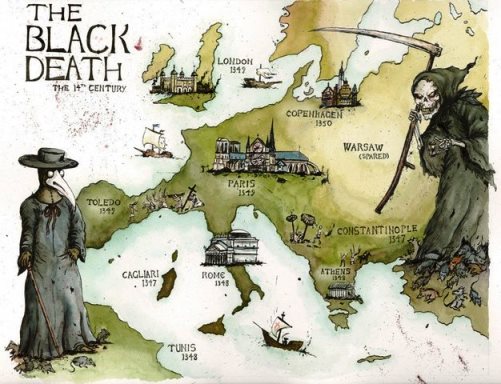

Plenty of readers and writers opt for the Middle Ages, an era

when the four horsemen of the Apocalypse - famine, war, death and pestilence -

ran roughshod over the landscape.

When I started writing historical crime I plumped for a

couple of hundred years later, London at the meeting-point of the 16th and 17th

centuries, the time of Queen Elizabeth and King James. Specifically the area

south of London Bridge which for centuries was the only bridge across the

Thames. It led to Southwark, a nest of bear-pits, brothels and playhouses, and

conveniently outside the control of the city authorities.

My sort of hero/detective is Nick Revill, fresh from the

country and desperate to make his way as a player by joining Shakespeare’s

company at the Globe Theatre.

When I was looking for interesting backdrops to set the books

against, one of the obvious and most dramatic was the plague. The Black Death

was the big outbreak, killing off an estimated third of the population of

England and the rest of Europe in the 14th century.

But the Black Death never went away. It bubbled beneath the

surface for generations, erupting every now and then. It was still bubbling and

erupting in Shakespeare’s lifetime.

Now we know that bubonic plague is spread by fleas carried by

rats and passed on to humans. The flea’s bite transmitted the plague bacteria.

Often, several days passed before the

first symptoms - the plague swellings or ‘buboes’ - showed themselves. By then

it was too late for our ancestors to do anything. Not that they would have

known what to do anyway.

The research for Mask of Night, the fifth book in my Nick

Revill series, threw up some intriguing and horrifying plague material. As usual,

the rich could escape because they had the means to move out of London for the

duration. The poor, in cramped housing, suffered most.

Lockdown really meant lockdown. I have a scene early in the book where Nick

Revill and a friend observe an alderman giving orders for a tumbledown house in

Southwark to be sealed up. The door was daubed with a cross in red paint and

then padlocked, with the people inside. It wouldn’t be opened again for forty

days. Anyone trying to help the occupants escape or even wiping off the red

cross would end up in the stocks or the ‘House of Correction’.

These methods were as useless as they were brutal. No one

noticed the plague-bearing rats scampering from slum to slum.

When the weekly death tolls in London passed a certain level,

the theatres were closed. An equivalent figure for deaths in the city now would

be well over 1000 a week.

At that point the players went on the road. They had to, to

practise their trade, to make money. In Mask of Night they travel to Oxford.

But the plague is there too, sometimes treated by physicians garbed in the

Elizabethan version of PPE, thick coats topped by the sinister bird-like masks

intended to protect the wearer from noxious air.

The cape and the bird-mask would be good cover for a

murderer, I thought. And where better to bury a body or two than among the mass

deaths produced by an outbreak of the bubonic plague?

Which makes you wonder when the first covid-19 thriller or

mystery is going to appear. Someone will be working on it now for sure.

(The Nick Revill Shakespearean thrillers have just been released by

Constable in new paperback/e-book editions.)