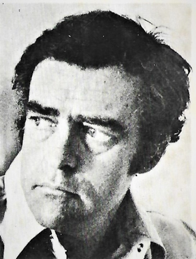

Alan Williams, 1935-2020

He was called ‘the master of adult excitement’, ‘the first real challenger to Ian Fleming’ and ‘a ruthless, compulsive storyteller’ though in another era, his famous godfather Noel Coward might have added ‘and he’s a very naughty boy.’

The son of actor and playwright Emlyn Williams, Alan Williams was born in 1935 and educated at Stowe, then Grenoble and Heidelberg universities before going on to King’s College Cambridge to read modern languages, graduating in 1957.

He was later to complain, tongue-in-cheek, that he was the only Cambridge student of his era not to be recruited by either MI6 or the KGB, which may have been because his extra-curricular activities as a student were so outrageous that each security service automatically assumed he had already been recruited by the other! As an undergraduate, he delivered penicillin to the insurgents in Budapest during the Hungarian uprising of 1956, managed to talk his way into East Germany ostensibly to play in a tennis tournament (he lost) and, whilst a delegate to a peace conference in Warsaw, helped smuggle a dissident Polish student to the West.

His first job on graduating was with Radio Free Europe in Munich, an organisation funded by the CIA, though he quickly returned to England for a career in print journalism initially with The Guardian but then as a foreign correspondent for the Daily Express. He was to report from many of the world’s ‘hot spots’, including Algeria, Vietnam and North Ireland, gaining a reputation for hell-raising and hard-living in dangerous settings. In later life he recalled ‘fond memories’ of playing poker with fellow foreign correspondent (and thriller writer) Gerald Seymour whilst under mortar fire, and how, during the civil war in Algeria, he would wear a white linen suit and white hat until he realised all the other reporters were moving away from him because he made such a good target. (He was also put on death lists by both the French intelligence service and the Algerian rebels.)

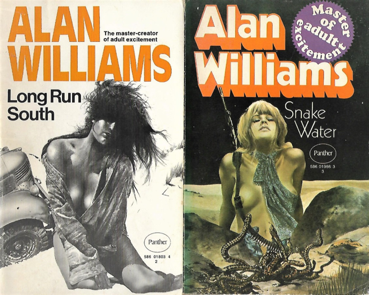

His experiences as a reporter gave him an eye for dangerous situations which he soon turned into fiction, his first thriller Long Run South appearing in 1962, the year of The Ipcress File and the release of the film of Dr No. Williams was 27 and seemed set for a long career in thriller fiction, his trademark take on the genre being the ‘Englishman abroad’, usually young, often a journalist, often randy and usually out-of-his-depth, entangled with villains and spies far more ruthless and violent than the hero, always in exotic locations ranging from North Africa to Iceland, South America to Cambodia.

Avoiding the temptation of a series hero – although all his protagonists were very similar – Williams created two superb villains who were to appear in several novels. One was the psychopath Rhodesian mercenary, Sammy Ryderbeit, the other the incredibly shifty French spy Charles Pol (a role surely for Sydney Greenstreet in a previous age).

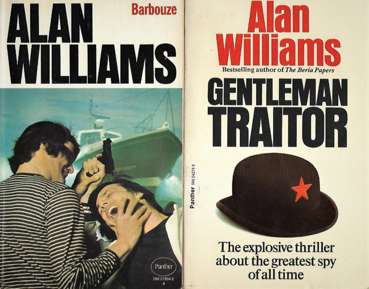

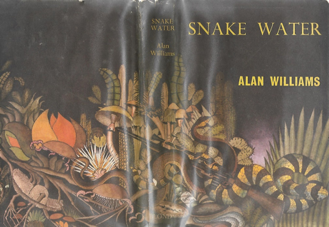

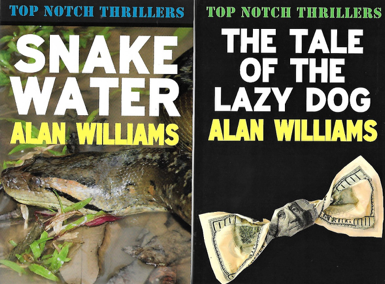

Pol made his first appearance in Williams’ second novel Barbouze in 1963 which one reviewer said lifted the author ‘into the top-rank of our young writers’, and Ryderbeit made his debut in Snake Water in 1965, for which Williams himself painted the jacket illustration.

The two were to appear together, cheerfully double-crossing each other (and all the other characters) in The Tale of the Lazy Dog in 1970.

By the 1970s, a new Alan Williams thriller was a major publishing event, not simply because they were good thrillers but because their subject matter automatically appealed to the headline writers. The Beria Papers not only postulated embarrassing historical revelations about the Soviet Union (in the middle of the Cold War) but also uncannily predicted the scandal of ‘The Hitler Diaries’ (wonderfully chronicled by a young journalist called Robert Harris).

In Gentleman Traitor in 1974, Williams dared to introduce that bogeyman of the British secret service, Kim Philby into spy fiction. Williams had met Philby once, in Beirut, shortly before the spy’s defection to Moscow where, according to a journalist who visited him there, he had a copy of the book (along with novels by John Le Carré and Len Deighton) on his bookshelf. Alan Williams was probably the first to use Philby as a fictional character but he was not to be the last and fellow thriller-writer John Gardner declared that Williams was ‘ahead of his time’.

He certainly was in one of his later novels, Holy of Holies, said to be a favourite of Robert Ludlum, in which he proposed the deliberate crashing of an aircraft by a terrorist organisation, into an international landmark (though not the Twin Towers).

But at the age of 46, Williams gave up writing fiction, though he was tempted out of retirement in 1992 to do an excellent job as editor of The Headline Book of Spy Fiction.

When I first got to know him, around 2009, it was to try and get some of his early work back into print as Top Notch Thrillers, the imprint of Ostara Publishing dedicated to reviving ‘great British thrillers which did not deserve to be forgotten’ for which I had just been appointed editor.

I had been surprised and appalled to find that most, if not all, of his thrillers were out-of-print and delighted when Alan happily agreed to let us reissue two of my favourites, Snake Water being one of the launch titles of Top Notch Thrillers.

Despite an American website assuming that he must be dead, Alan was “delighted to be treated as an author again” and insisted that I lunch with him at his club in Chelsea. It was possibly a unique occasion; an author taking his publisher out to lunch.

Plagued with ill-health and recovering from a stroke, Alan had been forced to give up alcohol. To accommodate this, he had bought cases of non-alcoholic beer which the club kept as his private stock. He did insist, though, on buying a bottle of wine for his guests so he could “enjoy watching them drink”.

In the sadly short time I knew him, he was a fund of stories about his own career as a newspaperman and about thriller writers who were his contemporaries. Many of the stories were scurrilous, possibly libellous, all were entertaining in the telling and he helped me formulate many of the ideas which were to emerge later in my Kiss Kiss Bang Bang personal history of the golden age of British thrillers.

When I asked him once who he really rated as a thriller writer, his answer, Winston Graham, rather surprised me. Having since followed up Alan’s tip and started to read Graham’s suspense fiction (not his bestselling ‘Poldark’ novels), I can see what he meant.

About five years ago Alan was diagnosed with vascular dementia and moved into sheltered accommodation where, aged 84, he contracted the Corvid 19 virus and died in mid-April.

There will be a memorial service for him once we come out of lockdown. In the meantime I will treat myself by reading the one Alan Williams novel I have never read, Dead Secret from 1980. It will almost certainly prompt me into re-reading my favourites form his backlist. For those unfamiliar with his work, Sapere Books are doing sterling work reissuing much of it in paperback and kindle formats.