Sarah Waters once said that many of her readers have suggested to her that her historical fiction is “full of lavatories”. She refers to such details as “poignant trivia”. As a result, in her research process, she embeds herself in the period she’s writing about, reading fiction, diaries, newspapers and letters and researching in great detail the small, domestic and ostensibly trivial details such as coins, locks and shoes. When doing my research for The Unpicking, my first major piece of historical crime fiction, it was this poignant trivia that I wanted to get right.

The Glasgow Lock Hospital for Unfortunate Females

The Unpicking started life as the creative writing element of a PhD thesis exploring the role of women between 1870 and 1920, particularly marginalised women whose lives are often missing from the records. It comprises three historical crime fiction novellas set in Scotland and featuring three generations of women. The first part, The Birdcage, is set in the late 1870s, and is the story of Lillias, a young, rich orphan who marries a man whose aim is to get his hands on her fortune. This he does by having her committed to an asylum. The Lock, set in the 1890s, features Lillias’ daughter, Clementina. At the start of the story, Clemmie is in a home for ‘wayward girls’ in Glasgow, but part of the story features the Glasgow Lock Hospital – a hospital for women with syphilis. The final part, The Turnkey, is set in 1919 and the protagonist, Mabel becomes one of Glasgow’s first (fictional) policewomen. So I want to talk a wee bit about some of the research I did for each of the stories.

A writer of historical fiction not only has the issue of writing a story which is entertaining but also needs to set it in context. I know what I eat for breakfast every morning, what my clothes are made of, or what Glasgow city centre smells like. I can get those across to a reader by using my own experience. I can’t do that with historical fiction, as the experience of my characters is not my experience. As a result, I don’t just need to know historical facts and figures; I also need to know the poignant trivia and telling detail.

I want my writing to be a sensory experience, and one where seemingly unimportant, intimate objects speak to character. Clothing, for example, might seem a trivial concern that is nothing to do with the story – and, in fact, has led to critics of historical fiction referring to it as “chick lit in petticoats”. However, if I have no knowledge of the clothes a woman might have worn, then I can’t understand how she moves through the space she inhabits, whether she is constrained by what she wears and the levels of discomfort she may have experienced – discomfort and constraint which may reflect and symbolise all aspects of her life.

When researching The Unpicking I lost myself for hours, quite happily meandering through a fascinating warren of research rabbit holes, googling, “Victorian cakes and how to make them”, “when were pockets invented?” and “what songs were popular in the 1870s?”. I now have hundreds of recipes for Victorian cakes and biscuits, with lovely names such as Rose Biscottine, Lemon Feather Cake and Tronchines. I even had a go at making Apricot Pithivier, the favourite sweetmeat treat of one of my characters. All of this research was to eventually make it on the pages as: “Clemmie walked past a cake shop.”

In fact, most of my research never made it onto the page, but I hope that finding out about things my characters might have eaten, scents they might have smelled, the paint colours on the walls, songs they might have heard and fabrics they might have touched, means that some of the colour and resonance of the period seeps into the words and hopefully, brings my stories to life.

Here I want to talk about some of the archival materials I used while researching The Unpicking, specifically, the records of individual women (or lack of them).

Part 1 - The Birdcage

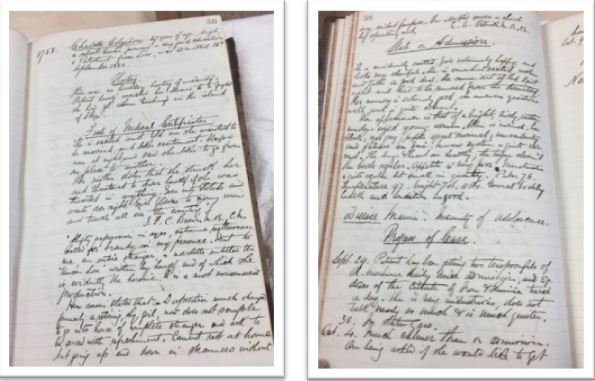

The main part of my research for The Birdcage was done in the archives of Stirling District Asylum, held at the University of Stirling. The records are fascinating, touching, sad, revealing and thought-provoking. A significant number of women were in the institution for many, many years. Many of the women’s notes state that their first “attack” was shortly after the birth of a child. And many have entries such as: “Brother a patient here”, “A sister died here”, “A paternal cousin is a patient here”. The case notes are pretty sparse (you might get entries in May, August and December one year and then February and November the following year) and the number which end “Patient died today” is really tragic. I focussed on records from around 1890, even though that’s after my story takes place. One of the reasons for this was that the records seem to be better kept and more detailed around this time. Another reason is that the authorities began to use photographs in the records and I found these very powerful, helping me to connect with the women even more. In 1890, the patients seem to be examined every couple of months. After that, it's about once a year unless there’s something happening with their treatment or situation. So these women (and, I presume, the male patients too), get a couple of sentences a year devoted to them. I managed to trace one woman through several books of case notes from her admission in 1869 to her death in the Asylum 1919 and it made me really sad to think of her being there for fifty years.

The notes from this period are written in different hands and each of those hands has a different style of writing. One (generally around May 1890) is efficient but kindly and he appears to treat the women as people. His entries are always followed (around September 1890) by a smaller, meaner hand. I did not like him at all. He describes patients like this: “Too demented to say what she feels, or if she feels at all…When pinched or pricked severely she makes no complaint and her facial muscles give no indication that she feels touch or pain…Coarse skin. Heavy, animal looking face.” He also makes the patients sniff pepper to see if they sneeze. And this man is totally obsessed with measuring the patients’ heads from every conceivable angle and describing their ears in minute detail, as though they are a collection of parts, rather than human beings.

I found the Stirling District Asylum archives really moving. I wanted to get an idea of how the women lived. The first part of The Unpicking - The Birdcage - is set in a private asylum to give me more flexibility over the plot, but the records were really useful – although often because of what was omitted, rather than what was included. The archives provide factual information about the patients: the size of their heads (obviously a very important factor for nasty doctor!), the colour and texture of their hair, their diagnosis. Occasionally, there are snippets of personal and personalising information, such as the notes for Charlotte Colquhoun, a 27-year-old schoolteacher from Luss who was admitted to the Asylum in 1882 and died there in 1895. She is described as a bright, lively young woman. The records state:

“She is excited and told me she wanted to be married, and likes excitement. Sleeps none at night, and said she likes to go from one place to another... Goes into hotels and waits overnight. Gives flowers to young men and travels all over the country.” Go Charlotte.

A different doctor continues:

“Called for brandy in my presence. Sent to me, an entire stranger, a novelette entitled the "Unseen Love" written by herself and of which she is evidently the heroine. It is a most nonsensical production. Her cousin stated that Disposition much changed: formerly a retiring, shy, girl, now does not scruple to go into house of complete stranger and ask to be served with refreshment.”

I think that Charlotte and I could have been pals. Little snippets of information such as this are both frustrating and intriguing, and also tell me something about the prevailing attitudes of the time.

Bellsdyke Hospital - Records of Charlotte Colquhoun,

Stirling District Asylum Archives: SD1/4/29, Record No, 1758, pp58-59

I sat in the archives at Stirling University and pored over the volumes over several days, taking notes, and photographing pages of the big, bound record books. It was tough to restrict myself to just a few years of records, because I wanted to find out more about all the women who were there, but I knew that I had to restrict myself: I wasn’t writing a factual history of Stirling District Asylum, after all.

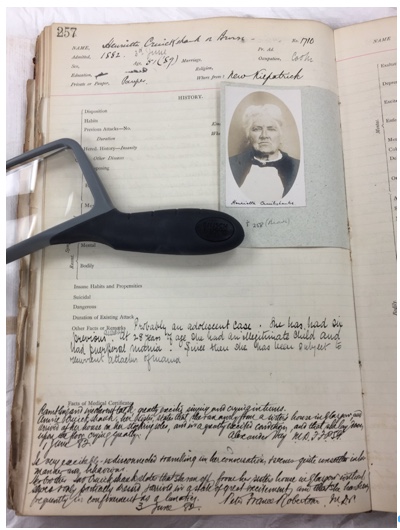

It was a daunting process to try and decide what to include in my story, but I kept being drawn back to the records for Henrietta Cruikshank. The man I referred to in my head as ‘nice doctor’ describes her as “a very striking, handsome, well-proportioned middle-aged woman. Her grey hair, abundant and pretty, coupled with her grey eyes lend a charm to her appearance when well and a wicked fiendish look when she is excited.” Even ‘nasty doctor’, after measuring everything that can be measured says, “She is fond of plucking flowers and decorating her friends with them.” I loved the image this gave me of Henrietta. He also notes that Henrietta has delusions of grandeur and says that she drew “the attentions of the young squire, that she has many children in the important parts of the world, had three husbands and was all her days annoyed by the male sex.” In 1906, at the age of fifty-eight, and twenty-four years after she entered the Asylum, Henrietta was released to Dumbarton Poorhouse, where I hope she got to spend her days plucking flowers with which to decorate her friends, although, sadly, I very much doubt it.

Bellsdyke Hospital – Records of Henrietta Cruikshank,

Stirling District Asylum Archives SD1/4/30 Record No.1710, p.257

Part 2 – The Lock

The lock hospital in Glasgow’s Rotten Row was one of Victorian Glasgow’s best kept secrets. I found out about it through a chance conversation with a former librarian at The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, and it was what inspired me to write The Unpicking. Anna told me about this mysterious and intriguing…hospital? Place of incarceration?...where women – and it was only women – were treated for syphilis. The sign above the door read Treatment – Knowledge – Reformation.

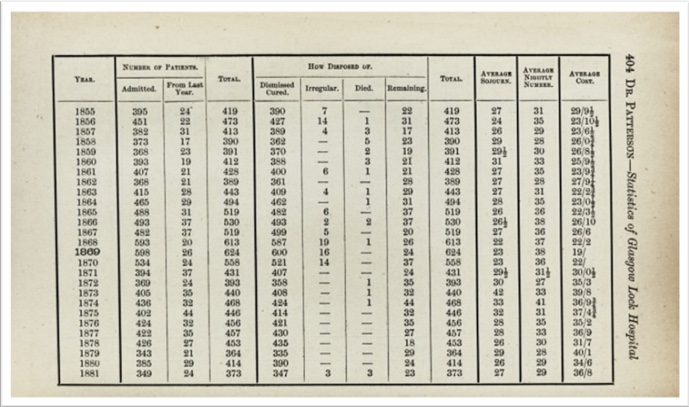

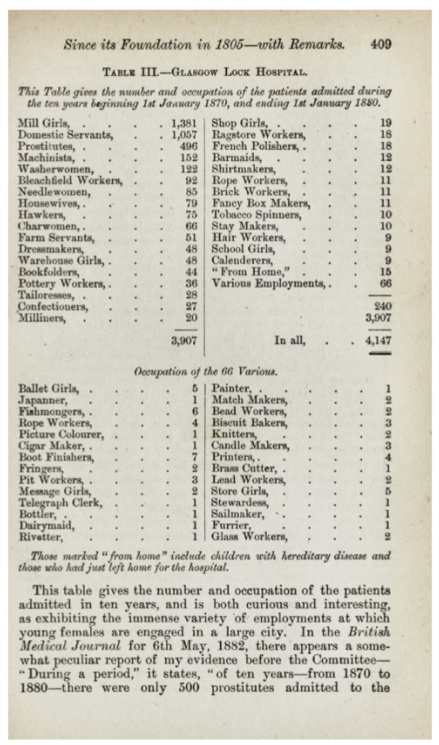

Sadly, there are few records. All that remains are reports which document how many women were admitted; how many left to employment, the workhouse, their families, or the grave; how much it cost to feed them and what they ate. The facts are starkly and boldly stated. In 1874, for example, 436 unnamed women and girls were admitted; 424 were dismissed as cured, one died; the average stay was thirty-three days; the average cost to care for them during their stay was 36s10d; porridge and milk was given twice daily, with a main meal of broth and beef, pea soup or rice and milk. Dr Patterson’s report also gives a list of occupations over a ten-year period between 1870 and 1880 (millgirls, hawkers, confectioners, ballet girls…) but with no other details of the women’s lives.

Excerpt from: Patterson, A., (1882). Statistics of Glasgow Lock Hospital since its foundation in 1805, with remarks on the Contagious Diseases Acts and on Syphilis. The Glasgow Medical Journal. No.6, December. p.4. Glasgow: Alex. MacDougall. Available at: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/hgszyqfj

Excerpt from: Patterson, A., (1882). Statistics of Glasgow Lock Hospital since its foundation in 1805, with remarks on the Contagious Diseases Acts and on Syphilis. The Glasgow Medical Journal. No.6, December. p.9. Glasgow: Alex. MacDougall. Available at: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/hgszyqfj

No ages are given, but the report states that, from a sample, ages were seven to thirty-nine. The youngest, incidentally, was noted by her doctor “as having contracted the disease herself”. One aspect touched on in The Lock is the “abominable superstition”: the belief that “if a man has contracted venereal disease and he can have connection with a virgin he will transmit that disease to her and himself escape free” (Royal Commission on Venereal Diseases, 1914).

My only other source for the lock hospital was the census. In 1891, twenty-three women were recorded as being in Glasgow Lock Hospital on the night of the census. They were between the ages of fifteen and thirty-nine, all designated ‘Patient’ and all occupations were recorded as ‘Prostitute’ except two recorded as domestic servants. In 1901, there were also twenty-three women recorded. They were aged between seventeen and forty-two, and all designated ‘Inmate’. This time their occupations were given: dressmaker, hawker, biscuit packer, tobacco worker, box maker, comie singer, servant. Using Ancestry.com I tried to trace all forty-six, but most of the names led to a completely dead end. None of the dates of birth were exact and no other details of the women are available. I wanted to tell the story of Glasgow Lock Hospital and the girls and women in it around the time of The Lock, but how could I? Other than a list of names occupations in a snapshot of two nights, ten years apart, I didn’t have anything to go on.

Part 3 – The Turnkey

The Turnkey is set in 1919 - not only shortly after some women have been granted the vote but also soon after the end of World War I, a war which has affected the whole of society and during which women proved themselves by doing men’s work. As a result, some women experienced freedoms they previously only imagined, and my protagonist, Mabel, can join a police force which would not have accepted her only a few years before, but still has to cope with being unwelcome. When I say she’s allowed to join, however, she doesn’t do so as a police officer, but as a “statement taker”.

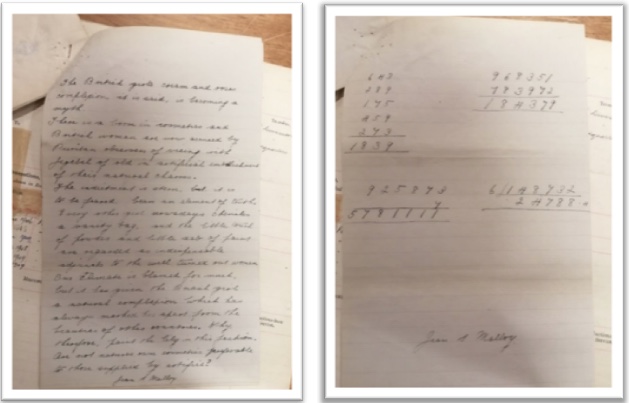

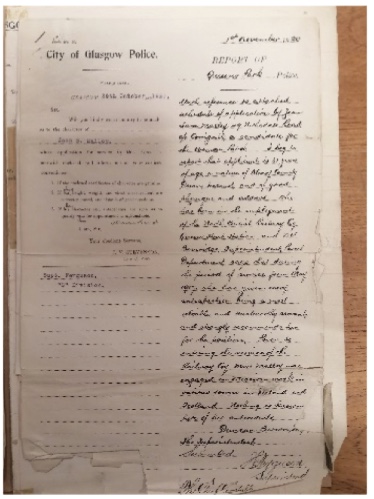

The records of some of the first women to join the police in Glasgow are held at the Mitchell Library’s archives. However, many of these individual records are missing, including those of Glasgow’s very first policewoman, Emily Miller. Most of what we know about Emily is from newspaper articles on her appointment (where the papers tied themselves up in knots, referring to her as a “woman policeman”) and parliamentary papers regarding the employment of women in the police. Records that are available include application forms, references, conduct and sickness records as well as hand amended forms changing ‘he’ to ‘she’. My favourite thing, though, are writing and arithmetic tests, which I have included reference to in The Turnkey. I gave Mabel the very same writing test that Jean Malloy was given in 1920 when she applied to be a Woman Patrol. I marvelled at the casual sexism of the topic she had to write about: “The British girl’s cream and roses complexion, it is said, is becoming a myth”.

Glasgow City Archives City of Glasgow Police records, Mitchell Library City Archives, SR22/38-70 Records of Jean Malloy, November, 1920

Glasgow City Archives, City of Glasgow Police records, Mitchell Library City Archives, SR22/38-70 - Records of Jean Malloy

Ethical Considerations

The ethics of using the records was something I thought very hard about. Any historical figures mentioned – such as Glasgow’s first policewoman, Emily Miller, or the Chief Constable, James Stevenson, both of whom are mentioned in the third part – The Turnkey – are either mentioned in passing or have only minor roles. In The Lock I have used real names for two women who were in Glasgow’s lock hospital in the censuses I looked at - Marion Cherry and Lillie Finlayson. Lillie particularly intrigued me, as her place of birth is given as Demerara in the West Indies. Marion and Lillie aren’t historical figures. On the contrary, they are forgotten and marginalised women, about whom almost nothing other than their names and places of birth is known. Even their ages aren’t exact. In this case, I’ve chosen to reclaim them from the archives. My reason for this is that, while I am unable to tell the stories of the real women concerned, I feel that I am, in some small way, marking their existence by the use of their names.

However, in the case of Henrietta Cruikshank in The Birdcage, my reasoning was different. I wanted to incorporate a friend for my protagonist, Lillias, in the asylum and Henrietta struck me as the perfect choice. So I took some of the aspects I found in her notes, as well as others from other patients and turned her into Lillias’ Henrietta Binnie. I chose not to use the real Henrietta’s surname. Unlike Marion Cherry and Lillie Finlayson, Henrietta Cruikshank does exist in the records as something more than a name. The Henrietta I wanted for Lillias is not the Henrietta of the archives. I was uncomfortable about reimagining the life of a real woman, yet ignoring the facts I do know about her. I didn’t want to use the full name of a real asylum inmate whose records contradict the story of my fictional Henrietta.

One of the major elements to the three parts of The Unpicking is in relation to the absence of individual women from the archives and the importance of fiction in bringing the characters to life as a way to give such women space on the page. That I was able to find out more about paint processes and wall coverings in private homes, asylums and public spaces than I could find out about the women who existed in those spaces is one of the things I thought about as I wrote.

Historical crime fiction is a wonderful way to consider marginalised and unrecorded lives and the gaps in the archives. It’s also a great way of considering women’s position in society and I can point to present day inequalities through comparisons with the past. Human and social issues are at the core of crime fiction and history is a great way to explore such topics.

The stories of my characters don’t stop in 1919, of course. What might this trilogy of novellas that takes place over a period of fifty years look like if I were to continue it for another fifty years? How does the mid-twentieth century treat the generations of women who come after Mabel? Or what would happen if I explored the gaps between the novellas? Each one takes place over a short period of time. The Birdcage starts in September 1877 and ends in August 1878; The Lock takes place over a few months in 1894; and The Turnkey starts with a specific historical event on 31st January 1919 and the story unfolds over the next few months. Thus, there are significant periods of the lives of my three main characters, as well as those of the supporting characters, which remain untold. The gaps between each one draw a parallel to the incompleteness of the records of ordinary women.

I learned a huge amount when writing The Unpicking. One of the best things I learned, however, was that I love doing historical research.

The Unpicking by Donna Moore

Fly on the Wall Press £10.00 pbk October 27, 2023