Ripster Revivals #3

An occasional series featuring authors and books which may have been unjustly forgotten, ignored or discarded.

Nevil Shute

I have never seen Nevil Shute described as a crime writer and in the lists of a publisher’s ‘other titles’ advertised in the last pages of old style paperbacks; his novels are invariably listed under General Fiction. Yet Shute himself was to admit that in his first three novels he was “obsessed with police action as a source of drama” involving, as they did, drug smuggling (Marazan), Soviet spies (So Disdained) and in Lonely Road, gun running into England to subvert the pending General Election.

Nor is he usually classed as a thriller writer, though several of his books are outstanding thrillers and he was a dab-hand at creating thrilling scenes, especially whenever boats or aeroplanes were concerned. His work was sometimes labelled as ‘prophetic’, which it certainly was, and occasionally ‘fantastical’ or ‘dream-like’ or simply ‘romantic’ – all of which would be fair comment – but the one label most readers and reviewers seem to agree on was that he was a damned good story-teller.

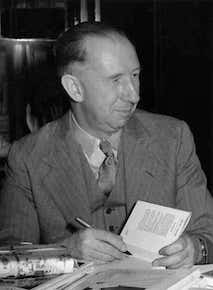

Nevil Shute Norway (1899-1960) was born in Ealing, the son of Arthur Hamilton Norway, a senior civil servant in the General Post Office who, in 1916, was Secretary of the Post Office of Ireland in Dublin. In the Easter Rising the 16-year-old Nevil volunteered as a stretcher-bearer for the Red Cross during the fighting around the city centre. After failing to gain a commission in the Royal Flying Corps, he served in the British army at the tail-end of World War I and then studied engineering at Oxford, graduating in 1922. Using a shortened version of his name as a pseudonym, he began writing fiction whilst working as an aeronautical engineer for Vickers, publishing his first novel Mazaran in 1926. His second and third novels were written as he worked on the design and construction of the R100 airship, on which he made a successful (return) journey to Canada. When the airship R101 (which Shute had nothing to do with) crashed in France on its maiden voyage to India, British involvement in airships ended and Shute turned his hand, and business brain, to designing aircraft, although the film version of Lonely Road, released in 1936, made him financially comfortable enough to give up the day job, though the thought probably never occurred to him. He honed his skills as a pilot and aeronautical engineer, establishing the company Airspeed Ltd which was to build the Airspeed Oxford, an aeroplane widely used by the RAF during World War II.

In the run up to the war, Shute produced three novels which certainly could not be classed as crime novels or thrillers and which reflected Shute’s experiences in aviation, as a conservative (sometimes very conservative) businessman and his growing interest in a spiritual or mystical outlook. In Ruined City (1938), the head of a small London banking house escapes a disastrous marriage by going walkabout in the wild north of England (having been driven north by his chauffeur). He eventually ends up, wrongly identified as a vagrant, in hospital in the town of Sharples, a former ship-building town ruined by the Depression, where he is treated kindly and resolves to help the town recover by providing employment, convinced that the only way out of poverty was the dignity of work (‘without work men are utterly undone’) – a theme which was to pervade many of his stories. His passion for flying combined with a mystical interpretation of history and folklore were at the heart of An Old Captivity (published in 1940), one of Shute’s most fantastical and romantic novels. An archaeological expedition to Greenland by seaplane stirs up hallucinations and dreams of the early Viking inhabitants of ‘Vinland’ – the east coast of North America – a subject which was to fascinate Shute and which he makes fascinating by contrasting the gruelling hardships of those early explorers with those of the pioneer aviators following a thousand years later.

In between these two novels, Shute produced a remarkable piece of work which brought him the label of ‘modern prophet’ for the first, but not the last, time. What Happened To The Corbetts was written in 1938 and published in April 1939, five months before the outbreak of WWII. In it, Shute predicted with terrifying accuracy the effects of aerial bombing on an English city, in this case Southampton. Shute’s concern was that ‘air raid precautions’ such as they were had concentrated on the use of a gas attack (memories of WWI being still fresh) and overlooked or underestimated the effects on a civilian population robbed overnight of shelter, water, electricity, telephones and fuel. The story follows the fortunes of the bombed-out Corbett family as they struggle through the chaos and their search for something as ‘normal’ as fresh milk for their children becomes a soul-destroying obsession. In an afterword to the book Shute wrote that whilst his story was fiction, he had set it in a real city in order to make his ‘forecasts’ as real as possible, although he fully expected to be in trouble with the Civil Defence and municipal authorities of Southampton.

When the war started for real, Shute was commissioned in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve – he was a keen sailor as well a pilot – but this did not put a dent in his output of fiction, rather it provided the inspiration for stories published during hostilities and for ten years after.

Landfall (1940) follows the plight of a young Coastal Command pilot who thinks he has attacked and sunk a German U-boat in the Channel, but was it in fact the British submarine which has gone missing in the same sea area? Pied Piper (1942), which many regard as his most moving novel, is the story of a retired English solicitor caught on holiday in France during the German invasion of 1940. Against all his better instincts he is persuaded to escort two English children on a perilous journey across a collapsing France. Never was an upper lip more stiff, nor, at the same time, more endearing. Pastoral (1944) is nothing more nor less than what the title suggests, a gentle love story set on an RAF bomber station which is also a hymn to the English countryside and everything those brave chaps and chapesses were fighting for.

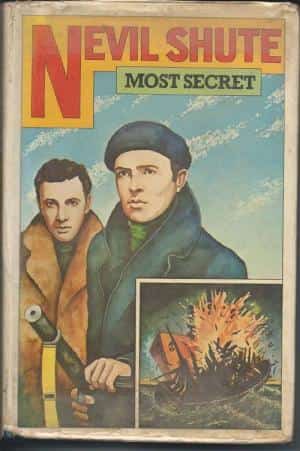

Probably Shute’s best – certainly the most gripping – wartime thriller, Most Secret was said to have been written in 1941 but for ‘reasons of nation security’ not published until 1945, much to the author’s annoyance. It almost certainly drew on Shute’s wartime experience working in special weapons research for the Royal Navy and centres on a small-scale raid using a disguised fishing boat armed with a flame-thrower, to destroy German E-boats guarding the fishing fleet of a small port in Brittany. The story is packed with the back stories of the commandos involved, frightening technical expertise (they develop a sort of primitive napalm) and a touch of mysticism as an old French priest insists that fire is the only weapon to combat the Nazis: “Before that power of fire all powers of heresy, idolatry, and witchcraft must recoil.”

The aftermath of the war and its lingering effects on people affected by it were clearly on Shute’s mind when he wrote The Chequer Board (1947). possibly his most famous novel A Town Like Alice (1950) and Requiem For A Wren (1955) by which time Shute had discovered, and fallen in love with, Australia. He had flown himself there and quickly decided to relocate his family. He died there in 1960.

Many of his post-war novels were to have Australian characters or settings, including his late masterpiece On The Beach (1957) which envisaged a nuclear war in the northern hemisphere and Australia as the last, if temporary, sanctuary from the approaching radiation. Stanley Kramer’s film of the book – starring Gregory Peck, Ava Garner and (a non-dancing) Fred Astaire – was only one of Shute’s novels to make the transition into successful movies, starting with Lonely Road back in 1936. The 1942 film of Pied Piper was Oscar nominated for Best Picture but lost out to that other patriotic romance Mrs Miniver; Michael Denison was the dashing RAF pilot in the war story Landfall in 1947; and James Stewart starred in a Hollywood version of Shute’s flying novel No Highway (in the sky) in 1951.

But the one film which wormed its way firmly into the post-war British psyche thanks to the involvement of National Treasure Virginia McKenna and heart-throb Peter Finch, was A Town Like Alice. Released in 1956, it is often reprised on British television and was, arguably, partly responsible for the hugely popular BBC series Tenko in the 1980s.

*

Through all Shute’s books there is the thread of men and women who are basically good, trying to do good things in awful situations created by crime, economic depression or war, and war, probably the most common theme, is never glorified. Indeed Shute highlights the dreadful mistakes made during wartime, particularly in Landfall and Requiem For A Wren (which puts a brilliant twist on a seemingly heroic act). He is also convincing when describing the loneliness and isolation of ordinary people involved in extraordinary events, often taking comfort by caring for pet dogs or, in one case, a rabbit.

Yes, he could be sentimental and the relationships between his young male heroes (invariably officers) and Other Ranks females (often Wrens) were always very proper for the time he was writing. That would also be a consideration for a modern, politically-correct editor who would recoil at Shute’s casual dismissal of several female characters as ‘not attractive’ or as ‘popsies’ not to mention a character’s motive being explained because ‘he was a Jew’ or a terrible attempt at a joke confusing semantic with semitic. Yet all Shute’s novels were reissued in 2007 and I am not aware that any were redacted or ‘revised’ to meet modern sensibilities.

They are undoubtedly old fashioned – but so are the novels of John Buchan and Ian Fleming, who ‘book-ended’ Shute’s writing career. We read them still, but probably not, or not so much, Nevil Shute, and yet we should – and for the same reason – they told bloody good stories and Shute was a particularly clever story teller.

He always had an interesting way of drawing the reader into a story. Lonely Road is introduced by a London solicitor who vouches for it to be the work, published posthumously, of the late Malcolm Stevenson and contains vital clues to the narrator’s war experiences which have shaped his psychology and explains his ruthless actions in the finale. So Disdained has a Preface claiming that the book is ‘based upon my (the narrator’s) written statement to the Foreign Secretary... [and] Reference to the official notes of my evidence before the Italian Secret Police...’ as well as to statements and documents provided by two characters who turn out to have links with the British secret service. An Old Captivity begins with a chance meeting during an interrupted train journey to Italy between a psychiatrist and pilot who admits to having strange dreams.

The story behind Pied Piper is told by a man ‘in my club’ in ‘did you hear about...?’ style, whereas Requiem For A Wren is put together like a detective story, the hero tracking down witnesses and taking statements to explain the suicide of his dead brother’s fiancée. Most Secret is told through the voice of a naval officer observing events. both military and very personal, dispassionately from afar, though never far enough to be unaffected by the heroic acts of defiance he has enabled.

_cover.jpg)

The way Shute draws the reader into his stories is very clever. He rarely adopts the omniscient narrator approach, rather he has a character letting the reader into a secret – ‘I heard this story the other day, you might find it interesting...’ It invariably was.

A born engineer and successful businessman, his fiction reflected his background and whilst his advocacy of liberal capitalism might grate on a cynical modern readership, no-one can doubt the authenticity of his dramatic flying sequences, particularly in his early books. With all things aeronautical (and small boats too), Shute was always in command of his material, which is hardly surprising as he was closely involved in all things aeronautical from the days of fragile biplanes, their pilots exposed to the elements, through giant airships and heavy bombers to jet passenger planes. In his novels he regularly uses the word ‘machine’ for aeroplane unless talking about a specific type, carrying this hangover from the early days of military aircraft right up to the nuclear age. But then, given his experience, he was allowed to.

Yet his obvious technical expertise is never allowed to swamp the main themes of his novels which are human rather than mechanical and reflect the tenderness and courage of his very human characters. Sometimes, however, his themes extended beyond normal human experience and dream sequences, often associated with pilots on long, lonely solo flights, push characters into the distant past or even the future, giving a fantastical flavour to his story.

Shute was said to have an interest in things paranormal and organised seances on Hayling Island in Hampshire during 1942, where he was working on secret weapons for the Royal Navy, including flame-throwers and ship-mounted rocket launchers. As there had been a trial under the 1735 Witchcraft Act that year following a séance where it was thought secret military information was being passed to enemy agents, sparking a minor media storm, it was likely that Shute – then a serving officer in a very sensitive research unit – would have been investigated by MI5 and warned off hosting any more dinner party seances.

Ripster Revivals 3 Nevil Shute.pdf