THE BACKGROUND

In 2020 I had planned to write a book set on the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, in the Arctic Circle. There were two elements to the story. One was the theme of climate change. The other was the reintroduction of two characters from the Lewis Trilogy.

I had planned to have Fin’s son, Fionnlagh, now 30, working on the archipelago. And when he is charged with murder, Fin comes to the Arctic to investigate and try to clear his son’s name.

My research trip for this book was scheduled for May 2020. I had booked flights, hotels, boat trips to the glaciers, tours of abandoned soviet coal mines. I had planned to visit the kennels of the working huskies who pull sleds across the frozen Arctic wastes. I had set up interviews, including one with the Governor of Svalbard.

But, then, in March of that year, Covid brought the world to a standstill as the virus spread like wildfire across the globe. My trip to Svalbard was cancelled. The book was dead in the water. I couldn’t write it without doing the research, and so the whole idea was abandoned.

I still had one book left to write in order to honour my contract with my publisher, Quercus, and so I spent the lockdown months writing “The Night Gate”, a book set largely in the area of France where I live - a story that required little in the way of location research.

But then came COP26 in Glasgow, the international conference on climate change. And the failure of politicians to take positive action so infuriated me that I decided I had to write another book. I resurrected the climate change theme of my abandoned Svalbard novel and reset it in my native Scotland. This was a completely new story, that required around four months of research and the end result was the hugely successful “A Winter Grave”.

All through the Spring of 2023, I couldn’t get the idea of Fin and Fionnlagh out of my head. Perhaps, I thought, I could resurrect that element of the planned Svalbard book, and take it back to the Isle of Lewis, employing my cast of characters from the Lewis Trilogy, twelve years on. Effectively coming full circle.

As I was developing this idea, two elements of life in the Hebrides forced their way into my consciousness through items in the news.

One was the increasingly critical media coverage of the processes of salmon farming, not just in the islands, but around Scotland and across the world. Huge death rates among fish in the cages, disease and infestations of sea lice. Overcrowding and pollution, the use of toxic chemicals, and the brutal treatment of the fish themselves.

The other was the recent stranding of more than fifty pilot whales on a beach on the east coast of Lewis, none of which could be saved from a slow and painful death, despite heroic efforts by both professionals and locals.

And slowly, these additional elements began to thread their way into my storyline. Of course, both subjects required extensive research.

THE STRANDING OF WHALES

Whales becoming stranded on Hebridean beaches is a relatively common occurrence, but the beaching of more than fifty pilot whales on Lewis last year was an almost unparalleled tragedy.

I interviewed Andrew Brownlow, the head of SMASS (the Scottish Marine Animal Stranding Scheme), which spearheaded attempts to re-float the creatures. He discussed in detail the circumstances that lead to strandings, and in particular the extended families, or pods, of pilot whales, and how the entire group will sacrifice itself for just one of its number. This worked in very well with the theme of my book, which was about family and sacrifice, and I found an echo of my story in this huge stranding event.

I learned how not only the experts, but the whole community, rallied to try to save the whales.

I went on then to talk to the island vet, Hector Low, who faced the unbearable task of having to euthanise those whales from the mass stranding which were still alive. The only way to kill creatures that size is to put a bullet in the brain stem, something which requires great skill on the part of the vet, but is also deeply traumatic. After all, like any doctor, a vet is charged with the saving of lives. But when out of the water for any length of time, a whale is unable to support its own weight, and slowly crushes itself to death, often in great pain. To put them out of their misery is an act of great humanity. But, of course, there is a human price to pay for it.

SALMON FARMING

My first line of research, into salmon farming, changed my life. Forever. I shall never eat salmon again, unless it is pulled wild from a river.

As part of my research into what is known as “aquaculture”, I obtained access to private videos taken by activists trying to draw public attention to the reality of modern salmon farming.

I saw salmon swimming lethargically around overcrowded cages, half eaten alive by sea lice.

I witnessed fish being sucked under pressure through huge tubes to be rinsed in fresh water to rid them of lice.

I saw farm workers smashing living fish with metal tubes as they writhed and tried to escape, blood spattering everywhere.

I was privy to drone footage of boats sucking dead fish from cages and dumping them into huge containers for disposal.

I saw skips of dead and diseased fish full of lice. Beside them were empty plastic containers of formaldehyde with warnings about the toxic, cancer-giving qualities of this poison being employed to rid the fish of lice. More than 50 tons of it have been used around Scotland, according to figures obtained through freedom of information.

I learned that a 2-acre fish farm discharging waste, pesticides and other chemicals directly into ecologically fragile coastal waters, can produce as much effluent as a town of 10,000 people.

I discovered that the flesh colour of farmed salmon is an unappetising grey, and that the fish are fed dyes to colour them pink.

There are 200 salmon farms in Scotland, with export sales of £600 million a year (worldwide it is an industry worth billions). But up to thirty million farmed salmon in Scottish cages are dying every year. Scottish salmon was the UK’s top food export in 2023, so it is hardly surprising that the government appears reluctant to enforce stricter regulations on their production and treatment.

THE STORY

Neither of these elements of my book comprise the story itself. They are only the backdrop to a way of life in the Hebrides in the 21st century, against which my father and son story is set.

A girl has been found dead. A young man - Fin’s son, Fionnlagh - charged with her murder. Did he kill her? Didn’t he? That’s what Fin must find out.

Check out Peter's events: https://geni.us/PETERMAY-EVENTS

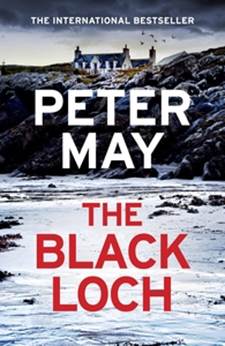

The Black Loch by Peter May

Quercus Publishing – 12/09/2024

Hardback – £22.00

Read Shots' review Here