As every school kid knows (or should), crime fiction begins in 1841 with the publication of Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘Murders in the Rue Morgue’. Except it doesn’t. Disparate tributaries feed the stream that emerges as a new genre in the mid-nineteenth century. Folklore, the Gothic Novel, the Newgate Calendar, all play their part. In the Scottish tradition, there’s another neglected wellspring of modern crime fiction: the ballads.

The Scottish ballads – that anonymous body of narrative verse, collected in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries but referencing events from much earlier – deal with violence, vengeance, murder, betrayal, kidnappings, hangings and drownings. And they treat this material in a starkly unsentimental style, marked by vivid imagery, swift transitions, biting dialogue and jet-black humour.

Sometimes the ballads anticipate the very form of crime fiction. ‘Bonnie George Campbell’, about a man who rides out one morning and never comes home, is a miniature murder mystery:

High upon Hielands and laigh upon Tay,

Bonnie George Campbell rode out on a day,

Saddled and booted, sae gallant to see,

Oh hame came his guid horse but never came he.

As the ballad progresses, we learn that Campbell was armed (‘a sword at his knee’) and that the empty saddle of his returning horse was covered in blood, but the mystery remains unsolved.

One of the darkest ballads, ‘Edward’, told entirely in dialogue, takes the form of an interrogation. Having been asked why his sword is covered in blood, Edward prevaricates, claiming that the blood is from his hawk and then his horse, before breaking down and confessing to the murder of his father. The interrogator is Edward’s mother and, in a shocking final twist, Edward curses her for having urged him to commit the deed. The interrogator, in other words, turns out to be the murderer’s accomplice; ‘Edward’ is the OG high-concept thriller.

In ‘The Twa Corbies’, two crows contemplate the body of a murdered knight. While they prepare to peck out his eyes and thatch their nest with his golden hair, we learn that the knight was murdered by his ‘lady fair’ who has taken another lover. The final couplet exemplifies the chilly worldview of the ballads: ‘O’er his white banes, when they are bare, / The wind sall blaw for evermair’.

Ballads like ‘The Twa Corbies’, ‘The Wife of Usher’s Well’ and ‘Sir Patrick Spens’ offer masterclasses in narrative technique. Later Scottish writers have been quick to learn their lessons. Muriel Spark, who wrote crime novels like The Driver’s Seat as well as The Ballad of Peckham Rye, was keen to acknowledge her debt: ‘the steel and bite of the ballads, so remorseless and yet so lyrical, entered my literary bloodstream, never to depart’.

The ballads have entered the literary bloodstream of Scottish crime fiction, too. Those pacy, cinematic poems, driven by dialogue, full of dramatic action and emotional intensity, have shaped the dark and bloody narratives of Rankin, McDermid, Mina and others.

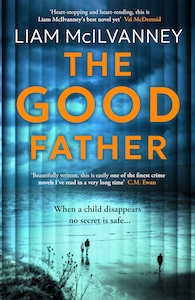

My own novel, The Good Father, draws deeply on the ballad tradition. The narrator, Gordon Rutherford, a lecturer whose seven-year-old son goes missing from the beach outside his house, is writing a book about the Scottish ballads. When the sniffer dog picks up his son’s scent and then loses it, Gordon’s mind turns to the ballads: ‘The trail had just given out, as if Rory had vanished into thin air, as if the ground had swallowed him up, like a figure in a ballad’.

Later, Gordon wonders if he can bring the detection skills of the literary critic to bear on his son’s disappearance: ‘My job was interpretation. I sifted evidence. I construed meanings. I inferred motives and intentions, pieced together an account of what was happening in a given work of fiction or a poem. Could I treat the disappearance like a ballad?’

As the family falls apart in its anguish, Gordon begins to see his wife Sarah as one of the grief-stricken women from the ballads: ‘She was like The Wife of Usher’s Well, who mourns her lost sons so bitterly that she coaxes them back from the grave’. As in the ballads, pain and desperation make my characters take steps they could never have dreamed they would contemplate.

In The Good Father I wanted to capture something of the ambience of the ballads, their abrupt transitions, the way people’s lives and assumptions can be turned on their heads in an instant. I wanted to write a different kind of thriller, one fueled by anguish and not just adrenaline, one in which the action is compressed but its impact extends over years. If I have succeeded, a large part of the credit will go to the hours I have spent ‘drinking the blude-red wine’ of the ballads.

SHOTS would like to thank Liam for writing this article, and Beth Whitelaw at Bonnier Books UK for organising it.

3rd July 2025 | ZAFFRE | £16.99

Publishing in Hardback, Audio & eBook

Read SHOTS' review