JOHN LAWTON has been described as one of ‘the fifty crime writers to read before you die’ and ‘the best writer of spy fiction you’ve never heard of ’. His novels, it is said, ‘contain a wealth of period detail, character depiction and background information that they are lifted out of any category. Every word is enriched by the author’s sophistication and irreverent intelligence, research and his wit.’

MIKE RIPLEY said none of those things, though he did review an early Lawton novel for the Daily Telegraph almost thirty years ago. Since then he has followed with interest the fortunes of the Troy family, Joe Wilderness and all the other characters historical or fictional, which have populated Lawton’s books. He has even managed to meet and occasionally talk to the famously reclusive author. Their latest conversation was fortunately recorded and is reproduced here with scarcely any redactions.

MR: Let’s begin with a bit of getting to know you —

JL: Thereby ignoring the last 25 years.

MR: I’ll pretend you didn’t say that. Five things you really don’t like?

JL: Travel, sport, cars, champagne, instant coffee.

MR: And five you do like?

JL: Schubert, Titian, Kate Atkinson novels, negronis, Florence.

MR: Substituting B.B. King, Caravaggio, Gore Vidal novels, a big Amarone and, okay, Florence, and it’s as if we were meant for each other. Favourite novelist?

JL: Nabokov, but you’re right, Vidal is worth more than a passing mention. He once said “Before ‘Myra’ there was the novel. After ‘Myra’ it was something else.” He was right.

MR: And … TV … a series you’d binge watch if only you weren’t working so hard?

JL: Dix Pour Cent, on France 2 and Netflix now. I know the writing is team work, but Fanny Herrero has put together an amazing team. It is the best-written series I’ve seen since Better Call Saul.

MR: Enough. I hear you’ve written some books?

JL: Yep.

MR: Was Black Out your first published book?

JL: First published novel — yes. But I’d worked on one of the early Films on 4 and written the novelisation. Appalling term, but the director told me he wanted more than a few inserted he/she saids. I think I delivered on that. Never did get to see the film though. I was out of the country when it was televised, and I don’t think it’s been repeated. I was in discussion with the director about a second film when I moved into what I’d call Channel 4 ’s heavy side layer, the kind of programmes they’d never dream of making today. The day after that I was offered a non-fic book on the year 1963, which I wrote between C4 programmes. So … Black Out was effectively my third book.

MR: It read (to me) as if it was already part of a series (in your head) with established characters, settings and plot threads. Was it, or did the idea of the Troy Saga develop from it?

JL: It was definitely conceived as a stand-alone. I began it in 1983. Took almost ten years to finish. By then I’d written — more importantly researched — the 1963 history which accidentally gave me the material for a series. I’m not sure if any writer begins with that notion. It's something publishers ‘do to you.’ You roll with it or you don’t.

MR: Was there any logic to the chronology of subsequent titles? For a time you were known as someone who wrote a series backwards.

JL: I’m still doing that. Current novel is set in 1905. No, no logic whatsoever. I’d finished the first three as a distinct trilogy and I’d paused. It was the late Diana Norman, ever my muse in these matters and better known now as historical novelist Ariana Franklin, who said, ‘go back and fill in the gaps.’ Only ever had one rule — I will not write about the 1970s. I was looking the other way when that decade happened. Besides, the music was awful — until Chrissie Hynde came along.

MR: Are you a thriller writer or a historical novelist whose books involve policemen and spies?

JL: The latter.

MR: Is British history 1930 - 1960 (?) your 'sweet spot' or comfort zone when writing?

JL: It probably began that way, and I think I read an interview with Ian McEwan (might have been David Hare) saying he wrote about his own era, and I took that to mean his formative years, and as McEwan and I are the same age, that means the Age of Austerity straight after WW2. The same might apply to Martin Amis and Kate Atkinson. I still have my ration book. Pinned above my desk. Memento mori? That said, I moved some way out of British history a while back. I’m as likely to write about Germany or Russia, and I’ve one book set entirely in the USA in the 60s …. the other formative years.

MR: But you weren’t there, in the Sixties?

JL: Of course not, but the civil rights movement was the most politicising series of events imaginable … in any country where there was a television set. Channel 4 sent me there a lot in the eighties. I even got to interview John Lewis. One of the most remarkable politicians of the Movement. In the nineties I got fed up with transatlantic flights and decided to live there. On and off that lasted about 12 years. Except for Black Out, all my early books were written in New York.

MR: Did your university studies have a bearing on your writing fiction? You read Politics at Essex didn’t you?

JL: No, I didn’t. I went to Essex as it was the only university in the country in the Sixties that offered a degree in American literature. Needless to say I was asked to vacate the premises after a while … and by the time they let me back in the course had been shoved into a single year and I realised I’d never get past Hawthorne … well … fukk that … so I looked around for something more interesting, and I found that I could do a crash course in Russian and study Russian lit as part of a degree in European literature, so instead of Tennessee Williams I found myself knee-deep in Chekhov, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy … and that did have a huge bearing on what I eventually wrote … and eventually taught. I stayed on at Essex far too long and taught Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. I might have written sooner if I’d left sooner.

MR: ‘Vacate the premises’? Are you saying Essex kicked you out?

JL: In ’69? Yes, but I’ve always found being fired advantageous. It makes the decisions that you’ve been putting off. I got fired a lot. I think I’ve been fired from most jobs I’ve ever had. No harm done.

MR: If you could have had any job or career you like, what would it be?

JL: Time travel permitting I’d be a Victorian naturalist specialising in amphibians. Newts and toads. How can anyone resist a word like Natterjack? Preferably after 1859.

MR: Why 1859?

JL: That was the year Darwin and Wallace presented their paper on evolution to the Linnaean Society in London, and ripped the lid off the biggest can of worms in history.

MR: Enough with the day-dreaming, we’re supposed to be talking about your Troy novels, though I suppose we’d better mention your second-string character Joe Wilderness. Where did Joe Wilderness come from, and more importantly why?

JL: Trying not to sound like a tosser …. I don’t find characters they find me. We can stop now if you like … that did sound like a tosser talking.

MR: No. Go ahead, dig yourself a hole.

JL: I wanted a change from Troy. Troy's an utter bastard. Joe is a nice guy. Albeit, Troy is a copper and Joe a crook. Troy is a philanderer, Joe a happily married man. I had the idea to take a scene from Black Out and rewrite it from the point of views of the other character. This was Troy’s first encounter with Swift Eddie … and I think the plot grew entirely from that … but Eddie is not a lead, he’s ‘best supporting actor.’

So along came Joe. One of my tutors at Essex had been drafted circa 1950 and was told he could do six months on the parade ground marching up and down or go to Cambridge, learn Russian and become a comms monitor for [MI] 5 or 6. I forget which. My twist was to make Joe an active agent, not an observer. The tutor, by the bye, was Peter Frank. He never did become an agent … he became the Kremlinologist (no, I did not make that word up) at Channel 4 News, which is where I worked with him years later.

MR: Is it just me or has anyone else noticed the regular cameos in your Troy novels of the anonymous "Fat Man" who seems to be something of an expert in pig-rearing?

JL: No, it's not just you. Although you may well have been the first. But it begins with Philip Roth.

MR: Weird. You’d better explain that.

JL: In Portnoy’s Complaint Portnoy laments that he is a perennial student and always reads with a pencil in his hand. That was me too … so I decided in my 20s that bedtime reading would be books without pencils and for years I read golden age crime in bed and left Levi-Strauss and Marshall McLuhan to daylight. I got hooked and my favourite character was Allingham’s Magersfontein Lugg. The pig man. I was, fortunately, at that time represented by Marje's agent, and published by the same publisher. Both said I could use him as long as I did not name him. She’s out of copyright in a few years, and at that point any old tosspot will be able to write Lugg stories.

MR: Your author blurbs are baffling.

JL: So?

MR: Are you trying to confuse people or are you really the curmudgeon some wicked critics make you out to be?

JL: Drop the plural. The wicked critic has always been you.

MR: Let me refine that. You say you belong to no societies and subscribe to no social media, rarely appear in public buying a pint of beer and often disappearing to a hill-top hideaway in Tuscany … sounds curmudgeonly to me.

JL: Hmmm … I saw my work in television as journalism. I was current affairs not news … all the same I successfully annoyed a lot of people, especially politicians … such fun — I used to love hearing from them — so belonging to any society was, and is, never ‘on’, as sooner or later you have to piss on your own doorstep. Social media? You’d have to have been deaf and blind not to see Muskrat and Fuckerberg coming twenty years ago. It’s pernicious, the legitimisation and universalisation of the school bully. It made Trump inevitable. It lifted Boris from a bit player in a Billy Bunter book to 10 Downing Street.

MR: Can I say you’re a political animal?

JL: If you like. It’s what I grew up in. It was immersive. My father, wisely in my opinion, turned down a crack at Westminster in ’51. But don’t ask me to state my present affiliation … not while there’s still a doorstep to piss on.

MR: I suppose we should talk about your new book, Smoke and Embers.

JL: If you insist.

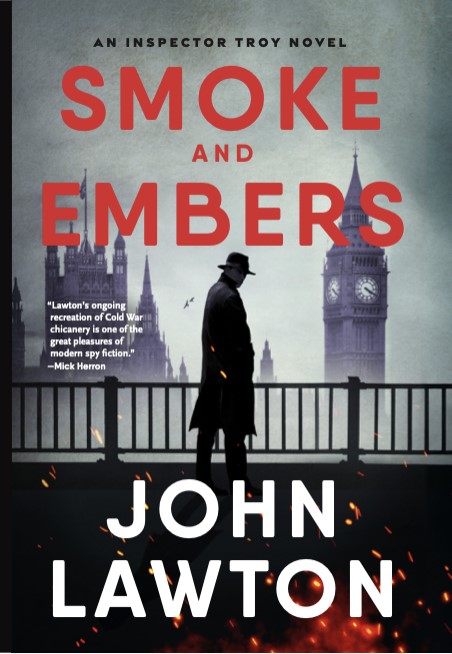

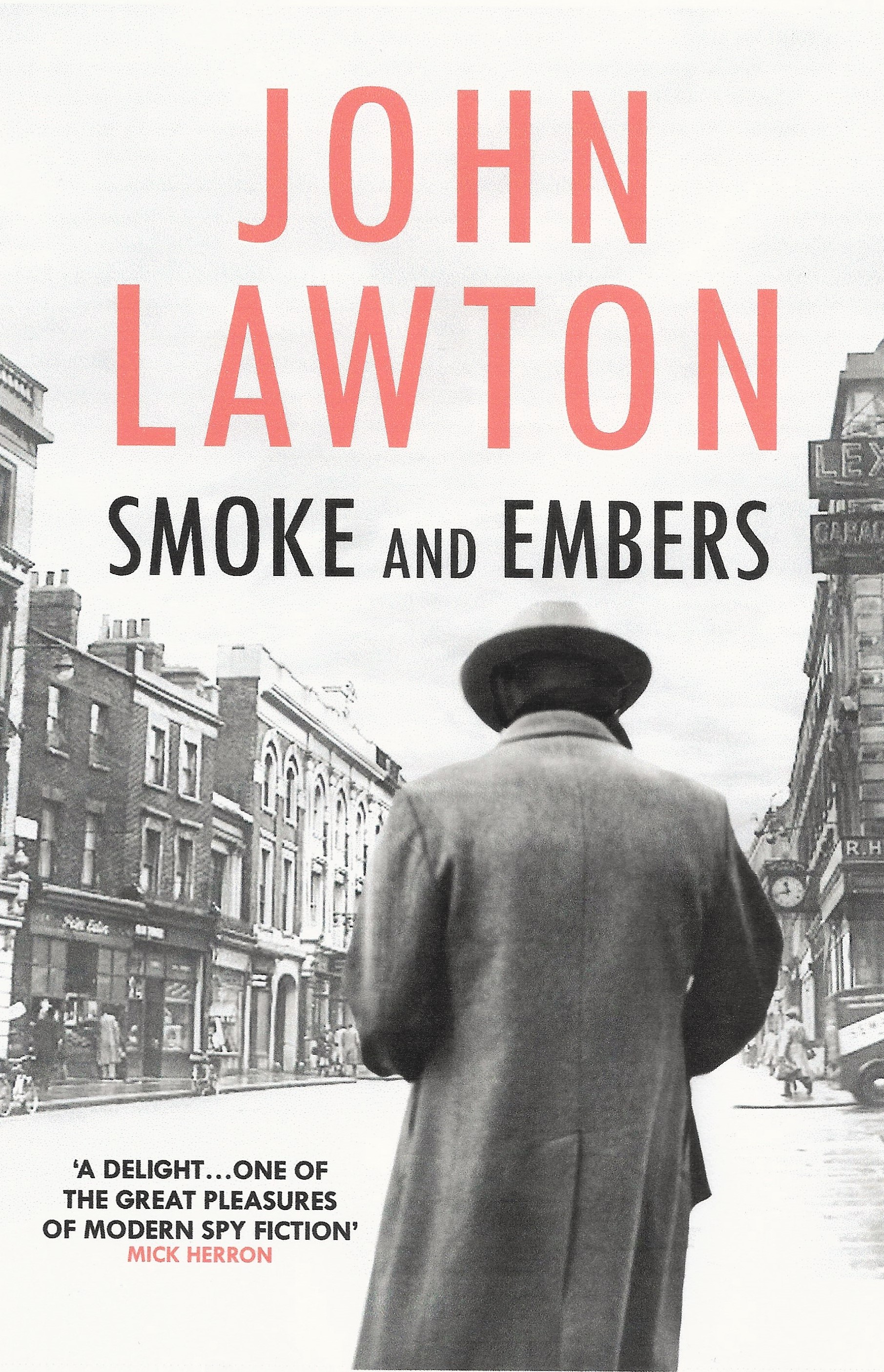

UK COVER

MR: And … ?

JL: It costs £16.99/$28

MR: Is that all???

JL: Apparently.

MR: God give me strength.

JL: OK. OK. It’s Troy 9. Smoke and Embers. I say Troy 9. There are a lot of other characters. Perhaps Troy is not the main one. But he is the solution to what takes place, if not the action. The novel spans seventeen years from the liberation of Auschwitz to the Eichmann trial. And I suppose it’s about … the fluidity of identity, about being able to assume and discard an identity. And Troy is central to that notion. I have long thought that the way to avoid writing the same novel over and over again is to keep shifting Troy’s rôle and to surround him with a cast of characters of almost equal ‘weight’. So this book is set in Poland, Germany, Israel, Argentina and … London … with a hefty number of players. He’s still a copper — I forget what rank — but he doesn’t really tackle murder-mysteries. He never did.

MR: Not sparing your blushes, ‘the fluidity of identity’ is a top notch description of the central theme, with characters sloughing off their original identities and pulling on new ones, and I’m not just saying that to prove I’ve read the damn thing. But with so many characters, time jumps and locations (from a body on a beach in East Sussex in 1950 to a body being cremated in Berlin in 1945 among them) plus a generous smattering of Russian, German and occasionally Italian, Yiddish and Hebrew, you don’t make life easy for your readers, do you?

JL: I don’t think that’s deliberate. It is simply the way I work. I record (not the right word, probably) what talks to me — and if, along the way, I provide more of a challenge than watching reality TV … so much the better.

MR: And next … ?

JL: Another collaboration with Zoë Sharp, or if we move quickly two collaborations. The first was ‘An Italian Job’ — quite a while ago now — and was played out as game of consequences, necessitated by the fact that we weren’t living in the same country at the time. The next is ‘Acid Factory’ — close to completion, but I cannot hustle for a date as Zoë has other commitments. The TV world seems to be beating a path to her door for her Charlie Fox novels. A man beat a path to my door, but it turned out to be just a bill for lawnmowing. However, next up … Bristol CrimeFest (UK) has asked for a contribution to their final anthology, so we’ll be in that as a double act. Abbott and Costello once more.

MR: Who’s on first?

JL: I’ll pretend I didn’t hear that.

MR: Then I’ll pretend I didn’t hear the one about the bill for lawnmowing. Just how much lawn do you have anyway?

JL: Move along, Mr Ripley.

MR: And when can we expect Troy 10?

JL: Don’t ask — just don’t ask. The ink is still wet on the contract.

MR: So there is a contract for another....

JL: Oh yes. I am too young and too handsome to retire just yet.

MR; So when you said earlier that your ‘Current novel is set in 1905’ (see, I was listening), were you talking about the next Troy? i.e. the one you are writing now whilst waiting for the under gardener to finish the lawn.

JL: Yes. Provisional title Dishonest Truths. Very much a Troy Prequel … 1905 – 1957.

MR: And finally….

JL: Are you sure?

MR: It’s chucking out time and you’ve made a ginger beer shandy last well over an hour, so what has disappointed you in over thirty years in print? You can leave out politics and marriage or we’ll be here till doomsday.

JL: Then I’ll stick to Arts.

MR: Good idea. Take your time. We’ve all of three minutes before last orders.

JL: Marianne Faithfull died a few weeks ago. Derided in her youth, greatly appreciated in later life, if only for one LP. The obits were legion. That set me thinking … not just about neglected rock stars (eg. will Elkie Brooks get the same acclaim? She just turned 80 and has never, I think, been recognised as just plain brilliant at what she does), but writers too. Richard Burns — is there a single book in print? Adam Zameenzad … same question. OK, they're both dead … Burns at 33, Zameenzad at 80 … both once 'spoken of in the same sentence as' Winterson or Okri, and I suspect, both forgotten. And Timothy Hallinan … my exact contemporary, and very much alive … one of America’s finest crime writers …. I’d rate him with Carl Hiaasen …. does he even have an English publisher?

MR: And if you could change one thing about your life? …. Marriage and politics still inadmissible here.

JL: Time travel again. I’d get born a bit sooner, say 1944. Then I’d have experienced the Sixties instead of watching from the outside with my nose pressed up against the glass. I’d get to London around 1964 or 65, instead of 1970 … and in 1970 I would leave London and never, ever return.

MR: You done?

JL: Yep.

MR: It’s your round.

Smoke and Embers (Inspector Troy series)

(US COVER)

Hardcover / eBook / Audiobook – 15 May 2025 from Grove Press UK