SPANISH

BANDITS AND CHINESE DETECTIVES

T.

Jefferson Parker & Henry Chang

Two

novels for American eyes only

I

jumped

at the chance to pick up a 'new' T. Jefferson Parker novel when I was

at the airport in New York recently, and as it turns out, it was a

good thing I did, because neither the book I bought, L.A.

Outlaws,

nor his subsequent Renegades,

has a UK publisher. This strikes me as being both unjust and amazing,

because Parker's had a string of impressive standalones (and the

three Lucy novels) published here, most notably 2005's California

Girls,

which was one of the two or three best crime novels of that year.

What interests me most about Parker is the way he's willing to take

risks; Fallen

could've been extremely gimmicky, but managed to avoid that fate, and

I have a similar feeling about Outlaws.

I

jumped

at the chance to pick up a 'new' T. Jefferson Parker novel when I was

at the airport in New York recently, and as it turns out, it was a

good thing I did, because neither the book I bought, L.A.

Outlaws,

nor his subsequent Renegades,

has a UK publisher. This strikes me as being both unjust and amazing,

because Parker's had a string of impressive standalones (and the

three Lucy novels) published here, most notably 2005's California

Girls,

which was one of the two or three best crime novels of that year.

What interests me most about Parker is the way he's willing to take

risks; Fallen

could've been extremely gimmicky, but managed to avoid that fate, and

I have a similar feeling about Outlaws.

Allison

Murrieta is a masked bandita who performs small armed robberies and

gives the proceeds to charity; she's claiming to be the descendant of

the legendary outlaw Joaquin Murietta, beheaded by a posse in 1853.

In reality, she's Suzanne Jones, a gorgeous school teacher who lives

in the countryside a long way from downtown LA. One night, about to

take down a sale of jewels, she witnesses an ambush and shootout

which leaves the stones with her, and a bad gangster on her tail.

Also on her tale is sheriff's deputy Charlie Hood, who is bedazzled

by Suzanne Jones and her muscle cars, and soon suspicious as well.

Where

Parker shines is in characterisation, and he does it here by

alternating between Suzanne/Allison in first person, and Charlie Hood

in third, which makes it easier for the reader to be carried away by

the pace of Suzanne's life of crime. You need to be carried away a

little, as Charlie himself is, because otherwise you might ask

yourself how, in the modern era of surveillance cameras and

computers, she's able to keep Charlie bamboozled enough to keep the

rest of the force off her back. But because the pace of the story is

so good, and the character so compelling, most readers will relax and

go with the flow.

Of

course it gets complicated: there are too many greedy people

involved, as is usually the case in jewel thefts, and Murietta may be

in over her head. Charlie is certainly in over his. But it is also to

Parker's credit that he resolves things with some flair, including a

bravura set-piece in a junkyard, but the ultimate resolution is the

kind of downbeat thing that smacks of realism, and more than

justifies whatever suspension of disbelief you may have felt

necessary to indulge Murietta's career. It's a superior piece of high

voltage action writing, a suspense thriller worthy of any on the

market, and it seems amazing to me that this is the book British

publishers would choose to leave untouched. By the way, Renegades

brings back Charlie Hood, who's an interesting study in

down-to-earth, not super-hero, cop, and I'm already looking forward

to that. It would be nice if I didn't have to go to America to read

it!

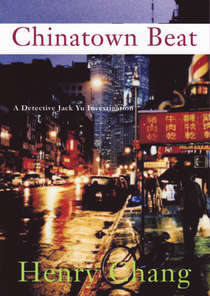

Meanwhile,

another American writer as yet unpublished here is Henry Chang. I

picked up Chinatown

Beat

through the mail after a fulsome review by Ron Rosenbaum, much of

whose journalism I admire, but whose literary hyperbole I shall take

with a grain or two of NaCl in the future. Actually, that's unfair to

Chang, whose book is an interesting take on police procedural, and

has a fascinating setting, but whose strongest point is actually his

femme fatale character, a Chinese black widow worthy of any in

hard-boiled fiction. But what works best in Chinatown

Beat are

mostly familiar elements: the cop alienated from his childhood

friends, the lone cop fighting an indifferent police force, the

inscrutable workings of the old Chinese tongs and the extreme

violence of the boys coming up.

Meanwhile,

another American writer as yet unpublished here is Henry Chang. I

picked up Chinatown

Beat

through the mail after a fulsome review by Ron Rosenbaum, much of

whose journalism I admire, but whose literary hyperbole I shall take

with a grain or two of NaCl in the future. Actually, that's unfair to

Chang, whose book is an interesting take on police procedural, and

has a fascinating setting, but whose strongest point is actually his

femme fatale character, a Chinese black widow worthy of any in

hard-boiled fiction. But what works best in Chinatown

Beat are

mostly familiar elements: the cop alienated from his childhood

friends, the lone cop fighting an indifferent police force, the

inscrutable workings of the old Chinese tongs and the extreme

violence of the boys coming up.

Chang

tries to take us deeper into Chinatown, but much of the time that

seems to consist mostly of using Chinese words and phrases, quickly

translated. He often seems to back off his best confrontational

scenes, and to some extent his characters often seem sketched in, as

if with a calligraphic brush, rather than painted more deeply. This

is true particularly because, although this is the story of Mona,

abused mistress of Uncle Four, and her plans of revenge and getaway,

the story's suspense builds from her use of the chauffeur, Johnny

Wong, aka Wong Jai or Kid Wong. And, as is usually true in such

tales, it is the character of the male, the victim with the

half-track brain and the one-track mind, which is the crucial one,

and it is here in particular that more depth would help. The rest of

the problem is that Mona never gets to play face to face against the

main character, who is Chang's Chinese detective.

Jack

Yu is an interesting detective, but the blossoming of his own romance

somehow seems at odds not only with the story but with the

characters, not as much him as the lawyer lady he befriends. This was

the first in a series by Chang, and with Yu transferred out of

Chinatown as the story ends, there is more opportunity for conflict

with the world of the gwailo, or white devils, within the department

as well as in the wider world. He's a character who can be developed

further, and perhaps with a more confrontational, if less

interesting, villain, he will be.

LA

OUTLAWS

by T.

Jefferson Parker,

Dutton (US) 2008, Signet (US paperback) 2009

CHINATOWN

BEAT

by Henry

Chang,

Soho Press (US) 2006

|

I

jumped

at the chance to pick up a 'new' T. Jefferson Parker novel when I was

at the airport in New York recently, and as it turns out, it was a

good thing I did, because neither the book I bought, L.A.

Outlaws,

nor his subsequent Renegades,

has a UK publisher. This strikes me as being both unjust and amazing,

because Parker's had a string of impressive standalones (and the

three Lucy novels) published here, most notably 2005's California

Girls,

which was one of the two or three best crime novels of that year.

What interests me most about Parker is the way he's willing to take

risks; Fallen

could've been extremely gimmicky, but managed to avoid that fate, and

I have a similar feeling about Outlaws.

I

jumped

at the chance to pick up a 'new' T. Jefferson Parker novel when I was

at the airport in New York recently, and as it turns out, it was a

good thing I did, because neither the book I bought, L.A.

Outlaws,

nor his subsequent Renegades,

has a UK publisher. This strikes me as being both unjust and amazing,

because Parker's had a string of impressive standalones (and the

three Lucy novels) published here, most notably 2005's California

Girls,

which was one of the two or three best crime novels of that year.

What interests me most about Parker is the way he's willing to take

risks; Fallen

could've been extremely gimmicky, but managed to avoid that fate, and

I have a similar feeling about Outlaws.

Meanwhile,

another American writer as yet unpublished here is Henry Chang. I

picked up Chinatown

Beat

through the mail after a fulsome review by Ron Rosenbaum, much of

whose journalism I admire, but whose literary hyperbole I shall take

with a grain or two of NaCl in the future. Actually, that's unfair to

Chang, whose book is an interesting take on police procedural, and

has a fascinating setting, but whose strongest point is actually his

femme fatale character, a Chinese black widow worthy of any in

hard-boiled fiction. But what works best in Chinatown

Beat are

mostly familiar elements: the cop alienated from his childhood

friends, the lone cop fighting an indifferent police force, the

inscrutable workings of the old Chinese tongs and the extreme

violence of the boys coming up.

Meanwhile,

another American writer as yet unpublished here is Henry Chang. I

picked up Chinatown

Beat

through the mail after a fulsome review by Ron Rosenbaum, much of

whose journalism I admire, but whose literary hyperbole I shall take

with a grain or two of NaCl in the future. Actually, that's unfair to

Chang, whose book is an interesting take on police procedural, and

has a fascinating setting, but whose strongest point is actually his

femme fatale character, a Chinese black widow worthy of any in

hard-boiled fiction. But what works best in Chinatown

Beat are

mostly familiar elements: the cop alienated from his childhood

friends, the lone cop fighting an indifferent police force, the

inscrutable workings of the old Chinese tongs and the extreme

violence of the boys coming up.